Campbell Thomson

Review Short: Peter Bakowski’s Personal Weather

Personal Weather by Peter Bakowski

Hunter Publishing, 2014

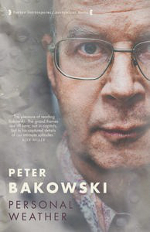

Bakowski looks into the lens in the photograph by Nick Walton-Healey on the cover of Personal Weather. The poems are also direct. They eschew simile, ambiguity, and the abstract. Were he an etcher, Bakowski’s work would be figurative with clear outlines and orderly perspective. There is no hesitation in his lines. His skies might be cloudy but there would be no obscuring storms of angst, only fugitive rays spotlighting the quirky in the mundane.

The preface to his 1995 prize winning book, In the Human Night, states that he was ‘Born with a hole in the heart to Polish-German parents in Melbourne on 15 October 1954 … On 21 January 1993 he survived an eight hour heart operation.‘

In this volume birds fluttered through the verses with unabashed lyrical abandon. Natural imagery abounded:

In the mean time there are more poems to write, I like to try to put a small truth in each one. Say, about the size of a mouse or a matchbox. (‘Self-portrait in East Melbourne flat, 22 June 1994’)

This is Bakowski’s credo. The poems presented as found objects the poet picks up on his daily walk:

The streets, of course are full of poems rushing off to work fretting at each kerb, waiting for the hiccup of each cursed traffic-light … Undress them carefully as you would, a peacock as you would, a panther (‘The Dictionary is just a beautiful menu, for Frank O'Hara’)

In Bakowski’s last collection, Beneath our Armour (Hunter 2009) he says ‘My aim as a poet is to write clear and accessible poems, to use ordinary words to say extraordinary things. No matter how many books I write in my life time they will all be about what it’s like to be a human being.’

The poems displayed international ambition. There were vignettes of writers such as ‘Portrait of Cyril Connolly’ and in another he had Sylvia Plath writing about Ted’s new lover.

Not all these life studies entranced but they reflect a working method:

learning the difference between the necessary and the overworked line. (‘Caspar Morton, portrait artist, talking about his life and work’)

Personal Weather, Bakowski’s seventh book, continues this minimalist, sharp eyed project. In ‘Self-portrait in the shadow of scalpels, Melbourne, 26 March 2013’, Bakowski is glad he ‘wasn’t born a century before/the common use of antiseptics,/blood transfusions,/general anaesthetization,/morphine and oxygen.’

There are five portraits of other writers, including Plath. Maybe there should be a century embargo on Plath poems. There is ‘A Melbourne letter poem to Ken Bolton’ and ‘A letter from Rebecca Cartello in Scarborough, England, to her sister Carla in Longreach, Queensland, 15 December 1955’. There are four poems about letters, including:

‘The letter Y’ invented the martini. (p 20)

There is a sextet of epigrams, including:

'The pickpocket' Wishing to reform he joins a nudist colony. (p 45)

There is a foreword by Barry Humphries, set out like blank verse. It could be taking the mickey. It reads, in part:

Most modern poetry like nearly all modern architecture is awful but these poems are good. Very good. (p 1)

A Spanish proverb prefaces the poems: ‘Tomorrow is often the busiest day of the week.’ A man with a serious heart condition may have a special relationship with tomorrow.

The poems in Personal Weather look similar: left justified, un-rhyming views through a 50mm normal lens with straightforward syntax. They have no interest in their own concreteness. They aim to mean. They aim beyond the delectation of other poets.

The book’s first poem is ‘City workers during morning rush hour, Collins Street’, alludes to John Brack’s painting of 5pm in the same street. The second stanza is:

What a gift is hunger. Because of it your ancestors left their caves, Explored plains, valleys, rivers, seas. These Adventures became paintings, songs, tall tales, family legends, headlines. There's the story of each person, on the trains, trams and street corners. How vulnerable you are, how strong you are. I want to reveal your Essence via the camera of this poem, as you swarm and Rush in the business district, glancing at your wristwatches. (p 3)

This has the yearning of Whitman without his music. It relies on lists and the close observation of a Cartier-Bresson.

Bakowski blogs poems and musings on poetry and his influences. He pays homage online in ‘One for Charles Bukowski’:

You've taught me to be lean in the poem, to say the thing directly, the way the hammer says things to the nail.

Online he discusses pruning and sifting his poetry: ‘I’ve realized in my twenty years of writing poetry I’ve now used the words ‘sparrow’ and ‘sofa’ enough.’

He talks about being inspired by crime fiction and biography. He describes writing poetry as ‘ambling with your thoughts on a long leash in the park of your skull.’

Do the words he finds in this park excite? His corner of the playground may not entice all players but there is a whittled, sly serenity in his best lines. From the book’s last poem, ‘Some observations and a wish, for Ron Padgett’ come:

During your life the speed at which your remove your clothes may vary. If pigs could fly, there'd be less bacon. To ants, a twig is a battering ram. May your mind resist the impulse to be a closed fist. (p 72)

One hundred years of games in literature do not trouble this work but there should be some quiet in our hubbub for Bakowski to be heard.